Watching Lola by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, is at times like watching a film by Claude Chabrol; and this is down to Armin Mueller-Stahl . Now Mueller-Stahl has never acted in any Chabrol films, but to me he looks like he should have. He is gentle, intelligent, comic and middle aged in a perfectly provincial and staid manner. In fact it is this provinciality that makes me think of Chabrol and this same provinciality that made him perfect for Lola.

I am aware, in fact that there is no connection with Chabrol here; but that doesn’t stop me. There’s no murder in this film; show me a Chabrol film with no murder in it; but Lola is much more gentle than many of the Fassbinder films before it, and by gentle I mean the ease with which one can become involved.

As the local building inspector Armin Mueller-Stahl is funny to us, and yet frightening to those around him, only due to their comic incompetence. The scene in which Von Bohm clears out his office for the first time, of paper, plants and the pornography of his predecessor, is devastatingly good. Armin Mueller-Stahl sweeps aside the previous timekeeping regime and gets to work! The project? None lesser than ‘the miraculous economic recovery of our social market economy’ – a phrase of course pronounced to the backing of Peer Raben’s military music.

The music also takes care of Mueller-Stahl when he is relaxing in Lola’s mother’s house, amid the new pastel shades of the German 1950s. Here there is sentiment, because here we think about the war (the past) and the future (Mariechen, Lola’s young daughter) – and here we see Mueller-Stahl, the perfect man, happy, easy-going, smart and funny – to all appearances a great catch.

The portrayal of the 1950s is one of the great successes of Lola – the purple lighting in Von Bohm’s every so modern bedroom – and the building – to the sound of drills in the background of otherwise unconnected scenes. With Fassbinder though, and this is the reason that he made so many films, and why we are still watching them – the milieu is secondary to human drama. So while Lola’s mother flirts with Von Bohm, Lola seduces Von Bohm and Von Bohm does not even know the two women are related and that the little girl he plays with in his guesthouse is Lola’s daughter. The tragedy which we are all waiting for is that Von Bohm does not know that Lola is a nightclub prostitute – and although it’s only a matter of time, when the shock comes, it hits us all hard.

The absurd purple light illuminating the Kummer home is strangely unnoticeable; even when it is added to by Von Bohm parading his ridiculous new suit – the suit of a suitor, anyway. It’s that ridiculous hunting suit that allows Von Bohm to fool himself into thinking he has different sides to his character. It’s a constant irony (and one that is never fully played out or exposed) that Lola, whom Von Bohm is courting is his landlady’s daughter. It’s pure farce and yet it plays as drama, simply because it’s so satisfying. And of course the landlady loves him too, it’s a great string to the film. When Fassbinder gets up close, the colours are also melting, although they are never really matched by the colour of Armin Mueller-Stahl’s eyes

On their first date, Lola and Von Bohm do what every good German couple do; they duet in church together. Von Bohm feels guilty because he feels far from innocent and Lola feels innocent, because she really is far from innocent, and this is as close as she could come. Both are lit in lilac, which shades and rolls over everything in the film – usually you can see it bathing the backs of actors’ heads – and even though this technique would never work outside, when characters are outside, the reds and purples are still usually visible shining out of the windows of nearby buildings. Having said that I wasn’t surprised to see that Fassbinder was still trying to light the bright summer days in lilac in Lola also; when Lola and Von Bohm sit on a bench outside the church on their ‘hike’ when the actors pass before the window, the sill can be seen to be faintly lilac and their shadows reveal the exact source of the light – and it ain’t the sun.

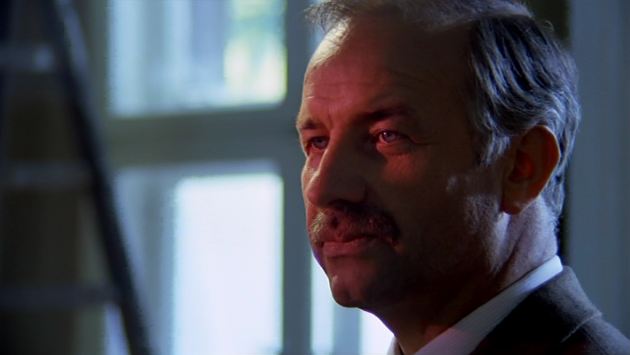

Mario Adorf and Armin Mueller-Stahl

It reminds me of what a completest, and what a complete package Fassbinder was. You will not notice it straight away, but the weird lighting in this film creates numerous effects, some fairy tale, some merely simplified cues. Lola and Von Bohm in the car at night, with Lola warning Von Bohm that he should leave town; and Von Bohm in ice blue light, and Lola in red hot. And yet they are side by side. It’s genius. Von Bohm is simply straight; he plays his violin, he plays at love, he attracts our sympathy because he is clever and primarily because he is goods to his secretary; but his faults will be revealed soon too.

Von Bohm is a dreamer, not normally a crime, but it is branded one here. When Von Bohm dreams about Lola he absentmindedly stirs his coffee with his cigarette. Overall, he may well be in the wrong town, and the wrong country, at the wrong time, something we suspect from the start.

The best Von Bohm acting given by Armin Mueller-Stahl is when he gets his brand new TELEFUNKEN. Obviously Fassbinder has great fun with it too, allowing some classic Gunther Kaufmann GI comedy English.

The television! Which sardonic Fassbinder examination of the 1950s would be without it? The characters’ enjoyment of the test picture; bathed in lilac the television delivery man adjusts the aerial; Das is ein teste spiel!

The best thing about the television in Lola is the extra button that Von Bohm doesn’t understand; but it’s there in case they ever get another channel . Armin Mueller-Stahl ‘s joke ‘Do you hear that Frau Kummer! We may get a second channel!’ only gets funnier and funnier, long after RWF passed away. It is a portrait of consumer satisfaction; a very serious and powerful image. Von Bohm lights a cigarette, the lilac lighting fantasises the living room, and there is the man of the future, watching the test card on the first ever generation of television.

Poor Von Bohm cracks up however, actually goes mad, first at the sight of the brothel which he finds unbelievable, and then faced with the impossibility of his job. It’s sad, but he really is that innocent. While Von Bohm believes the town has been asleep, it is really living it up in these garish late night haunt, and by the time Armin Mueller-Stahl as Von Bohm sees Lola singing Caprifischer, his laughter has already died. It’s not that his character comes to appreciate Bakunin, but he has his own revolution between nightfall and dawn, and in the best style of provincial dramas, he wrecks his revenge on the entire municipality.

When Armin Mueller-Stahl declares he will ‘destroy and defeat!’ Schuckert, have we further shades of Hitler here? And when he tries to be a real man like the rest of them, drunken and lecherous, it is of course sad, and a signal that the end is very near indeed. These emotions cost him very dear in the end, and the last third of Lola really comes through as a love story – maybe Fassbinder’s best – and this is largely down to Armin Mueller-Stahl.

Armin Mueller-Stahl at Wikipedia.